System of units

The International System of Units<ref>SIbrochure8th</ref> (abbreviated SI from Lang-fr<ref>Resolution of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures establishing the International System of Units</ref>) is the modern form of the Metric system and is generally a system of Units of measurement devised around seven base units and the convenience of the number ten. The older metric system included several groups of units. The SI was established in 1960, based on the metre-kilogram-second system, rather than the centimetre-gram-second system, which, in turn, had a few variants. The SI is declared as an evolving system, thus prefixes and units are created and unit definitions are modified through international agreement as the technology of measurement progresses, and as the precision of measurements improves.

SI is the world's most widely used system of measurement, which is used both in everyday Commerce and in Science.<ref>Official BIPM definitions</ref><ref>Essentials of the SI: Introduction</ref><ref>An extensive presentation of the SI units is maintained on line by NIST, including a diagram of the interrelations between the derived units based upon the SI units. Definitions of the basic units can be found on this site, as well as the CODATA report listing values for special constants such as the Electric constant, the Magnetic constant and the Speed of light, all of which have defined values as a result of the definition of the metre and ampere.

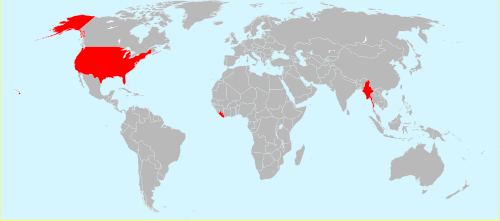

In the International System of Units (SI) (BIPM, 2006), the definition of the metre fixes the speed of light in vacuum c0, the definition of the ampere fixes the magnetic constant (also called the permeability of vacuum) μ0, and the definition of the mole fixes the molar mass of the carbon 12 atom M(12C) to have the exact values given in the table [Table 1, p.7]. Since the electric constant (also called the permittivity of vacuum) is related to μ0 by ε0 = 1/μ0c02, it too is known exactly.– CODATA report</ref> The system has been nearly globally adopted with the United States being the only industrialized nation that does not mainly use the metric system in its commercial and standards activities.<ref>Cite web</ref> The United Kingdom has officially partially adopted metrication, with no intention of replacing Imperial units entirely. Canada has adopted it for many purposes but imperial/US units are still legally permitted and remain in common use throughout many sectors of Canadian society, particularly in the retail food, buildings trades, and railways sectors.<ref>Weights and Measures Act</ref><ref>Weights and Measures Act, accessed January 2012, Act current to 18 January 2012. Canadian units (5) The Canadian units of measurement are as set out and defined in Schedule II, and the symbols and abbreviations therefor are as added pursuant to subparagraph 6(1)(b)(ii).</ref>

Contents

History

The Metric system was conceived by a group of scientists (among them, Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier, who is known as the "father of modern chemistry") who had been commissioned by the Assemblée nationale and Louis XVI of France to create a unified and rational system of measures.<ref>Cite web</ref> On 1 August 1793, the National Convention adopted the new decimal Metre with a provisional length as well as the other decimal units with preliminary definitions and terms. On 7 April 1795 (Loi du 18 germinal, an III) the terms gramme and kilogramme replaced the former terms gravet (correctly milligrave) and grave and on 22 June 1799, after Pierre Méchain and Jean-Baptiste Delambre completed their survey, the definitive standard metre was deposited in the French National Archives. On 10 December 1799 (a month after Napoleon's coup d'état), the metric system was definitively adopted in France.

The desire for international cooperation on Metrology led to the signing in 1875 of the Metre Convention, a treaty that established three international organizations to oversee the keeping of metric standards:

- General Conference on Weights and Measures (Conférence générale des poids et mesures or CGPM) – a meeting every four to six years of delegates from all member states;

- International Bureau of Weights and Measures (Bureau international des poids et mesures or BIPM) – an international metrology centre at Sèvres in France; and

- International Committee for Weights and Measures (Comité international des poids et mesures or CIPM)—an administrative committee that meets annually at the BIPM.

The history of the metric system has seen a number of variations, and has spread around the world, to replace many traditional measurement systems. At the end of World War II, a number of different systems of measurement were still in use throughout the world. Some of these systems were metric-system variations, whereas others were based on customary systems. It was recognised that additional steps were needed to promote a worldwide measurement system. As a result, the 9th General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM), in 1948, asked the International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM) to conduct an international study of the measurement needs of the scientific, technical, and educational communities.

Based on the findings of this study, the 10th CGPM in 1954 decided that an international system should be derived from six base units to provide for the measurement of temperature and optical radiation in addition to mechanical and electromagnetic quantities. The six base units that were recommended are the Metre, Kilogram, Second, Ampere, degree Kelvin (later renamed Kelvin), and Candela. In 1960, the 11th CGPM named the system the International System of Units, abbreviated SI from the French name, Lang. The seventh base unit, the mole, was added in 1971 by the 14th CGPM.

One of the CIPM committees, the CCU, has proposed a number of changes to the definitions of the base units used in SI.<ref name="draft">Cite web</ref> The CIPM meeting of October 2010 found that the proposal was not complete,<ref>Cite web</ref> and it is expected that the CGPM will consider the full proposal in 2015.

Units and prefixes

The International System of Units consists of a set of units together with a set of prefixes. The units are divided into two classes—base units and derived units. There are seven base units, each representing, by convention, different kinds of physical quantities.

| Unit name | Unit symbol | Quantity name | Quantity symbol | Dimension symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metre | m | Length | l (a lowercase L), x, r | L |

| Kilogram <ref group=note>Despite the prefix "kilo-", the kilogram is the base unit of mass. The kilogram, not the gram, is used in the definitions of derived units.</ref> | kg | Mass | m | M |

| Second | s | Time | t | T |

| Ampere | A | Electric current | I (an uppercase i) | I |

| Kelvin | K | Thermodynamic temperature | T | Θ |

| Candela | cd | Luminous intensity | Iv (an uppercase i with lowercase non-italicized v subscript) | J |

| mole | mol | Amount of substance | n | N |

| ||||

Derived units are formed from multiplication and division of the seven base units and other derived units<ref name=SI>Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor, (2008), Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI), (Special publication 811), Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology, p. 3.</ref> and are unlimited in number;<ref>SIBrochure8th</ref> for example, the SI derived unit of speed is metre per second, m/s. Some derived units have special names; for example, the unit of resistance, the ohm, symbol Ω, is uniquely defined by the relation Ω = m2·kg·s−3·A−2, which follows from the definition of the quantity Electrical resistance. The Radian and Steradian, once given special status, are now considered dimensionless derived units.<ref name=SI/>

A prefix may be added to a unit to produce a multiple of the original unit. All multiples are integer powers of ten, and beyond a hundred(th) all are integer powers of a thousand. For example, kilo- denotes a multiple of a thousand and milli- denotes a multiple of a thousandth; hence there are one thousand millimetres to the metre and one thousand metres to the kilometre. The prefixes are never combined, and multiples of the kilogram are named as if the gram was the base unit. Thus a millionth of a metre is a micrometre, not a millimillimetre, and a millionth of a kilogram is a milligram, not a microkilogram.

In addition to the SI units, there is also a set of Non-SI units accepted for use with SI, which includes some commonly used non-coherent units such as the Litre.

Writing unit symbols and the values of quantities

- The value of a quantity is written as a number followed by a space (representing a multiplication sign) and a unit symbol; e.g., "2.21 kg", "Val", "22 K". This rule explicitly includes the percent sign (%). Exceptions are the symbols for plane angular degrees, minutes and seconds (°, ′ and ″), which are placed immediately after the number with no intervening space.<ref name='BIPM style'>Cite book</ref><ref name='nist style'>Cite web</ref>

- Symbols for derived units formed by multiplication are joined with a centre dot (·) or a non-break space; e.g., N·m or N m.

- Symbols for derived units formed by division are joined with a solidus (/), or given as a negative Exponent. E.g., the "metre per second" can be written m/s, m s−1, m·s−1, or <math>\textstyle\frac{\mathrm{m}}{\mathrm{s}}</math>. Only one solidus should be used; e.g., kg/(m·s2) and kg·m−1·s−2 are acceptable, but kg/m/s2 is ambiguous and unacceptable.

- Symbols are mathematical entities, not abbreviations, and do not have an appended period/full stop (.).

- Symbols are written in upright (Roman) type (m for metres, s for seconds), so as to differentiate from the Italic type used for quantities (m for mass, s for displacement). By consensus of international standards bodies, this rule is applied independent of the font used for surrounding text.<ref name=BIPM2006Ch5>Cite book</ref>

- Symbols for units are written in Lower case (e.g., "m", "s", "mol"), except for symbols derived from the name of a person. For example, the unit of Pressure is named after Blaise Pascal, so its symbol is written "Pa", whereas the unit itself is written "pascal".<ref>Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor, (2008), Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI), (Special publication 811), Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology, section 6.1.2</ref>

- The one exception is the Litre, whose original symbol "l" is unsuitably similar to the numeral "1" or the uppercase letter "i" (depending on the typeface used), at least in many English-speaking countries. The American National Institute of Standards and Technology recommends that "L" be used instead, a usage common in the US, Canada, and Australia (but not elsewhere). This has been accepted as an alternative by the CGPM since 1979. The cursive ℓ is occasionally seen, especially in Japan and Greece, but this is not currently recommended by any standards body. For more information, see Litre. The litre is not an SI unit per se and is expressed in SI terms as a cubic decimeter, i.e., dm3.

- A prefix is part of the unit, and its symbol is prepended to the unit symbol without a separator (e.g., "k" in "km", "M" in "MPa", "G" in "GHz"). Compound prefixes are not allowed.

- All symbols of prefixes larger than 103 (kilo) are uppercase.<ref>Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor, (2008), Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI), (Special publication 811), Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology, section 4.3.</ref>

- Symbols of units are not pluralised; e.g., "25 kg", not "25 kgs".<ref name="BIPM2006Ch5" />

- The 10th resolution of CGPM in 2003 declared that "the symbol for the decimal marker shall be either the point on the line or the Comma on the line." In practice, the decimal point is used in English-speaking countries and most of Asia, and the comma in most continental European languages.

- Spaces may be used as a Thousands separator (Gaps) in contrast to commas or periods (1,000,000 or 1.000.000) in order to reduce confusion resulting from the variation between these forms in different countries. In print, the space used for this purpose is typically narrower than that between words (commonly a thin space).

- Any line-break inside a number, inside a compound unit, or between number and unit should be avoided, but, if necessary, the last-named option should be used.

- In Chinese, Japanese, and Korean language computing (CJK), some of the commonly used units, prefix-unit combinations, or unit-exponent combinations have been allocated predefined single characters taking up a full square. Unicode includes these in its CJK Compatibility and Letterlike Symbols subranges for back compatibility, without necessarily recommending future usage.

- When writing dimensionless quantities, the terms 'ppb' (parts per billion) and 'ppt' (parts per trillion) are recognised as language-dependent terms, since the value of billion and trillion can vary from language to language. SI, therefore, recommends avoiding these terms.<ref name='BIPM style'/> However, no alternative is suggested by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM).

Writing the unit names

- Names of units follow the grammatical rules associated with common nouns - in English and in French they start with a lowercase letter (e.g., newton, hertz, pascal), even when the symbol for the unit begins with a capital letter. This also applies to 'degrees Celsius', since 'degree' is the unit. In German however, names of units, in common with all nouns, start with a capital letter.<ref>Cite book</ref>

- Names of units are pluralised using the normal English grammar rules;<ref name=Taylor>Cite journal</ref><ref>Cite journal</ref> e.g., "henries" is the plural of "henry".<ref name=Taylor/>Rp The units Lux, Hertz, and siemens are exceptions from this rule: they remain the same in singular and plural form. Note that this rule applies only to the full names of units, not to their symbols.

- The official US spellings for deca, metre, and litre are deka, meter, and liter, respectively.<ref name='deka'>Cite web</ref>

Realisation of units

Metrologists carefully distinguish between the definition of a unit and its realisation. The definition of each base unit of the SI is drawn up so that it is unique and provides a sound theoretical basis on which the most accurate and reproducible measurements can be made. The realisation of the definition of a unit is the procedure by which the definition may be used to establish the value and associated uncertainty of a quantity of the same kind as the unit. A description of how the definitions of some important units are realised in practice is given on the BIPM website.<ref>SI Practical Realization brochure</ref> However, "any method consistent with the laws of physics could be used to realise any SI unit."<ref>SIbrochure8th</ref> (p. 111).

Related systems

The definitions of the terms 'quantity', 'unit', 'dimension' etc. used in measurement, are given in the International Vocabulary of Metrology.<ref>Cite web</ref>

The quantities and equations that define the SI units are now referred to as the International System of Quantities (ISQ), and are set out in the ISO/IEC 80000 Quantities and Units.

Conversion factors

The relationship between the units used in different systems is determined by convention or from the basic definition of the units. Conversion of units from one system to another is accomplished by use of a conversion factor. There are several compilations of conversion factors; see, for example, Appendix B of NIST SP 811.<ref name=Taylor/>

Cultural issues

The near-worldwide adoption of the metric system as a tool of economy and everyday commerce was based to some extent on the lack of customary systems in many countries to adequately describe some concepts, or as a result of an attempt to standardise the many regional variations in the customary system. International factors also affected the adoption of the metric system, as many countries increased their trade. For use in science, the SI prefixes simplify dealing with very large and small quantities.

Many units in everyday and scientific use are not SI units. In some cases these units have been designated by the BIPM as "non-SI units accepted for use with the SI". <ref>BIPM - Table 6</ref> <ref>BIPM - Table 8</ref> Some examples include:

- The units of time (Minute, min; Hour, h; Day, d) in use besides the SI second, are specifically accepted for use according to table 6.<ref>BIPM - Table 6</ref>

- The year is specifically not included but has a recommended conversion factor.<ref>NIST Guide to SI Units - Appendix B9. Conversion Factors</ref>

- The Celsius temperature scale; kelvins are rarely employed in everyday use.

- Electric energy is often billed in kilowatt-hours, instead of megajoules. Similarly, battery charge is often measured as milliampere-hours (mA·h), instead of coulombs.

- The Nautical mile and knot (nautical mile per hour) used to measure travel distance and speed of ships and aircraft (1 International nautical mile = Gaps m or approximately 1 minute of latitude). In addition to these, Annex 5 of the Convention on International Civil Aviation permits the "temporary use" of the foot for Altitude.

- Astronomical distances measured in astronomical units, parsecs, and light-years instead of, for example, petametres (a light-year is about 9.461 Pm or about Gaps m).

- Atomic scale units used in physics and chemistry, such as the Ångström, Electron volt, Atomic mass unit and barn.

- Some physicists prefer the centimetre-gram-second (CGS) units, or systems based on physical constants, such as Planck units, Atomic units, or geometric units.

- In some countries, the informal cup measurement has become 250 mL. Likewise, a 500 g metric pound is used in many countries. Liquids, especially alcoholic ones, are often sold in units whose origins are historical (for example, pints for beer and cider in glasses in the UK —although pint means 568 mL; Jeroboams for champagne in France).

- A metric mile of 10 km is used in Norway and Sweden. The term metric mile is also used in some countries for the 1500 m foot race.

- In the US, blood glucose measurements are recorded in milligrams per decilitre (mg/dL), which normalises to cg/L. In Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Oceania, and Europe the standard is millimole per litre (mmol/L) or mM (millimolar).

- Blood pressure is usually measured in MmHg(≈Torr).

- Atmospheric pressure in government weather reports is measured in InHg in the USA,<ref>Current Weather Conditions: DENVER INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT</ref> and in the SI unit hPa in Australia,<ref>Australia Mean Sea Level Pressure Analysis</ref> UK<ref>Met Office Weather Units</ref> and most other countries.

The fine-tuning that has happened to the metric base-unit definitions over the past 200 years, as experts have tried periodically to find more precise and reproducible methods, does not affect the everyday use of metric units. Since most non-SI units in common use, such as the US customary units, are defined in SI units,<ref>Mendenhall, T. C. (1893). "Fundamental Standards of Length and Mass". Reprinted in Barbrow, Louis E. and Judson, Lewis V. (1976). Weights and measures standards of the United States: A brief history (NBS Special Publication 447). Washington D.C.: Superintendent of Documents. Viewed 23 August 2006 at http://physics.nist.gov/Pubs/SP447/ pp. 28–29. </ref> any change in the definition of the SI units results in a change of the definition of the older units, as well.

International trade

One of the European Union's (EU) objectives is the creation of a single market for trade. To achieve this objective, the EU standardised on using SI as the legal units of measure. As of 2009, it has issued two units of measurement directives, which catalogued the units of measure that might be used for, amongst other things, trade: the first was Directive 71/354/EEC<ref>Cite web</ref> issued in 1971, which required member states to standardise on SI rather than use the variety of cgs and mks units then in use. The second was Directive 80/181/EEC<ref>Cite web</ref><ref>Cite web</ref><ref>Cite web</ref><ref>Cite web</ref><ref>Cite web</ref> issued in 1979, which replaced the first and gave the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland a number of derogations from the original directive.

The directives gave a derogation from using SI units in areas where other units of measure had either been agreed by international treaty, or were in universal use in worldwide trade. They also permitted the use of supplementary indicators alongside, but not in place of the units catalogued in the directive. In its original form, Directive 80/181/EEC had a cut-off date for the use of such indicators, but with each amendment this date was moved until, in 2009, supplementary indicators have been allowed indefinitely.

Chinese characters

In Japanese: Individual Chinese characters exist for some SI units, namely metre, litre, and gram, with the prefixes from kilo- (1000) to milli- (1/1000), yielding 21 (3×7) characters. These were created in Japan in the late 19th century (Meiji period) by choosing characters for the basic units – 米 "metre", 立 "litre", and 瓦 "gram" – and for the prefixes – 千 "kilo-, 1000", 百 "hecto-, 100", 十 "deca-, 10", 分 "deci-, 1/10", 厘 "centi-, 1/100", and 毛 "milli-, 1/1000" – and then combining them to form a single character, such as 粁 (米+千) for kilometre (in the case of no prefix, the base character alone is used). The entire metre series, for example, is 粁, 粨, 籵, 米, 粉, 糎, 粍. The symbols for the metric units are internationally-recognised Latin characters.

In Chinese: The basic units are 米 mǐ "metre", 升 shēng "litre", 克 kè "gram", and 秒 mǐao "second". Some sample prefixes are 分 fēn "deci", 厘 lí "centi", 毫 háo "milli", and 微 wēi "micro". These are not combined into a single character, so for example centimetres are simply 厘米 límǐ.